#WalkBikeForward: Join us on our journey honoring key moments and people that have shaped our field as we celebrate 20 years of creating active, healthy communities.

Earl Blumenauer was first elected to Congress in 1996, representing the Portland area. For 20 years he’s been a champion of biking, walking and livable communities, along with other environmental and social issues.

From Portlandia to Houston and Birmingham

Active communities are no longer a fringe movement. What we’ve been doing in Portlandia for years has been studied, copied, improved upon in communities around the country, and we’ve now passed the tipping point. Bike commuting nationally has increased more than 60 percent since 2000, and more than doubled in many cities. Nearly 70 communities have bikeshare, from Los Angeles to Birmingham. In Houston, Texas, $200 million has been spent on bike paths in Houston. Communities see walkable development as a prerequisite to attract talent to the workforce, demanded by Millennials and Baby Boomers alike. Active communities, planning for people, not cars, the 20-minute neighborhood — these concepts are ubiquitous, guaranteed to catalyze private investment and make people happy.

An important element of success is getting it right the first time. We had a bikeshare experiment in the 1990s here in Portland that I think left people a little hesitant about trying it again. Now with Biketown bikeshare, we’ve been able to learn from the success and mistakes of other systems. The DC streetcar is finally running, but after years of setbacks and mismanagement, the community is very skeptical about expanding it into a larger system. If the projects work from the beginning and people see the benefit, they’re eager to build off that success.

It’s also been important not to rush into it, or force livability on a community that’s not ready. I’ve always said that we should “build no line before its time,” and I think that’s been critical. Milwaukie, Oregon, rejected light rail for years, worried about “Portland creep,” but now the residents, local leaders, and business folks love the Orange Line that opened just last year. When we build active communities patiently, diligently, and collaboratively it makes a difference. It serves as an example, and people want more of it.

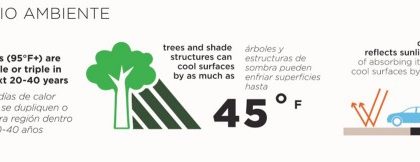

Another huge factor in providing some of the enthusiasm for active communities at the local level is climate change. It’s been a grassroots-led movement, and we’ve made great strides. However, when you look at what we need to do to reverse course, and deal with the reality that transportation is the largest contributor of carbon emissions, and that long range planning calls for 20 percent reduction in automobile use, all of a sudden it gets a lot easier to help people walk, bike, and take transit. Active communities are a logical response to climate change, and we’re going to continue to see it framed in those terms

Big Changes Ahead

We’re going to see transformational changes in the next 20 years. We’re watching two very disruptive forces colliding — one is changing demographics and population growth, largely in urban areas, the other is the rapidly emerging technology of autonomous vehicles. The technology has the opportunity to completely refigure the urban environment. Fleets of electric, autonomous vehicles used for carsharing will mean a decline in car ownership, less congestion because cars travel just inches away from each other. Whole swaths of right-of-way and public space devoted to cars could be reclaimed. You don’t need 12-foot lanes for cars that are only 7-feet wide. Street parking can be taken back, used for protected bike lanes and wider sidewalks. Parking structures will be obsolete and could be redesigned as parks or affordable housing. With less space and resources devoted to cars that sit unused 95 percent of the time, we create more incentives for people to be active, walk or bike. By taking human error, which is responsible for up to 90 percent of traffic collisions, completely out of the equation, our streets and communities will be safer for everyone. Preparing for and integrating autonomous vehicles will let communities accommodate growing demand and population without adding miles of new highway that we don’t want and shouldn’t build.

As a nation we need to address the resource question. Across public infrastructure, from water systems to road maintenance, federal investment has declined and local revenues have been increasingly taxed by competing spending priorities. Right now, cities are forced to choose between expanding pre-K options for kids or building sidewalks, while lead pipes and aging sewer systems continue to remain out of sight and out of mind. That is a false choice that we shouldn’t have to make.

At the federal level, we should be taking advantage of low interest rates, an engaged private sector, and increasing public demand, to make serious investments in public works. Perhaps the best example of the broken federal investment model is the gas tax, unchanged since 1993, and now worth almost 40 percent less due to inflation and fuel efficiency. It’s increasingly regressive, as drivers of more expensive electric and hybrid cars pay less and less to drive the same roads, while those with older cars pay more and more. The Highway Trust Fund runs about a $14 billion annual deficit, and instead of planning for the future or changing the way we spend scarce federal resources, Congress spends all its time figuring how to fill the gap in the gas tax, just to get back to zero. The potential benefits of driverless cars, larger investment in transit and intercity passenger rail, extending and completing a bike network — none of this can happen without funding certainty and a better, more reliable partner at the federal level.

Active communities are not just about building bike lanes and providing transportation options. The federal government and local governments can do a much better job ensuring that there is affordable housing and economic opportunities near transit, so everyone can experience livable communities.

Why I Like to Bike

Personally, I chose not to bring a car to Washington, DC, when I went to Congress. I’ve biked all but a few days in my nearly 20 years there. It’s something I’m very proud of, and biking every day is a great way to start the day off in a better mood. And, I’m probably a few pounds lighter as a result! In Portland, it’s been inspiring to see us grow into a world-class biking city, and having the opportunity to experience transit and biking with my grandchildren has been a real joy for me.

I’m biased, of course, by having witnessed the progress in Portland and seeing how transportation choices have revolutionized our community and economy. Every year, I take the opportunity to go to the Portland Community Cycling Center’s Holiday Bike Drive, where they distribute hundreds of bikes to children who otherwise couldn’t afford them, and give them the training and education they need to be safe on their new bikes. It inspires me every year, and I do what I can to help expand programs like these to provide bikes to more kids to get them started on bikes young. But being the “bike guy” in Congress, I have the privilege of hearing from people all over the world who tell stories about how cycling has given them access to jobs, recreation, and community.

I knew Oregon would become a leader for active communities as a young legislator. I voted for Senate Bill 100 to support urban growth boundaries and land use planning in 1973. We were intentional about creating walkable communities and have seen increased demand for urban living in recent years. It’s been exciting to watch the national movement build from here.